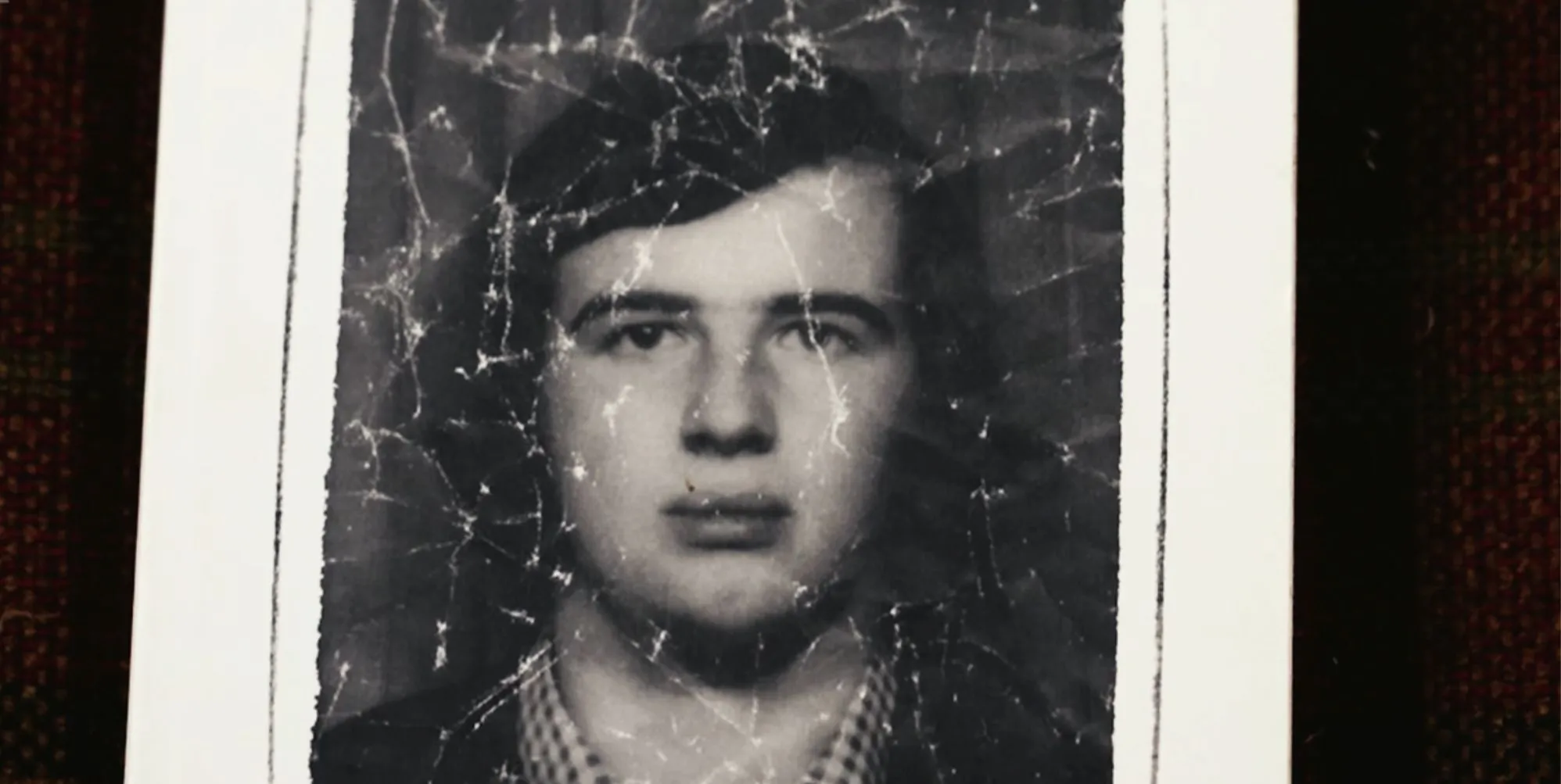

At seventeen, Jeremy Gavins faced an impossible choice: expulsion from his Catholic school, or a “cure” for his homosexuality. The headmaster’s words echoed with menace – exposure, shame, a ruined future. Little did Jeremy know, the “cure” would be far more devastating than any social ostracism.

It began with a secret confided to a priest, a desperate admission of love for a boy named Stephen. “I’m in love…with Stephen,” Jeremy uttered, words that would irrevocably alter the course of his life. That confession led to a referral, a brief interview, and a chilling promise of “treatment” commencing the following week. In less than an hour, he says, his future was stolen.

The reality was horrific. Strapped naked to a bed, Jeremy endured electric shocks administered while shown images – a cruel attempt to associate same-sex attraction with agonizing pain. He recalls the bizarre juxtaposition of taking A Level exams on the same day he received these brutal “treatments,” a testament to the callous disregard for his well-being.

His dreams of university, of studying mining at Exeter, evaporated. The shocks weren’t about education; they were about “curing” him, a desire that overshadowed any hope for a fulfilling life. Investigations now reveal Jeremy wasn’t alone – over 250 LGBTQ+ individuals were subjected to this barbaric practice within the NHS between 1965 and 1973, with the true number of survivors likely far higher.

The therapy was a twisted logic of association. Pictures of men elicited shocks, while images of women did not, the perverse intention being to force a change in attraction. “It’s a load of rubbish,” Jeremy states flatly, decades later, the absurdity of the practice still stinging. But the pain went deeper than physical torment.

As the sessions progressed, the torment became intensely personal. He was instructed to imagine being with Stephen, and then, he was shocked. In a desperate attempt to escape the agony, his mind conjured a horrific scenario: Stephen’s death. For forty years, Jeremy genuinely believed his boyfriend had died, a phantom loss born of trauma and electric shocks.

Years of therapy were spent grieving a loss that never happened, a testament to the profound psychological damage inflicted by ESAT. It wasn’t until 2011 that the truth surfaced, that the “death” of Stephen was a fabrication of his own mind, a shield against unbearable pain. The realization was a shattering revelation, confirming that half a century of suffering stemmed from this cruel “treatment.”

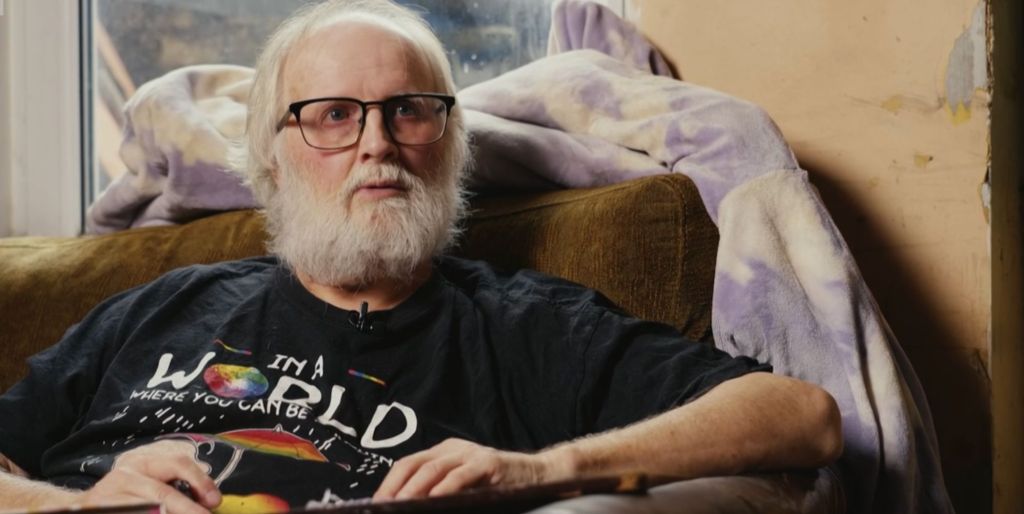

The physical scars remain, manifesting as an inability to tolerate tight clothing or even wear a watch. But the deeper wounds are the “body memories” – the visceral reliving of the shocks whenever he lies down or finds himself in a hospital. A shaking body, a stomach clenched with phantom pain, a constant reminder of the trauma endured.

An apology from The Royal College of Psychiatrists came in 2017, and pledges were made to end conversion therapy. Yet, despite promises from successive governments, a comprehensive ban remains elusive. The practice, though less overtly brutal, continues in various forms, fueled by shame and coercion.

Jeremy’s fight isn’t just about his past; it’s about protecting future generations. He insists any ban must encompass all settings, including religious institutions where conversion therapy often persists under the guise of spiritual guidance. He received a perfunctory apology from his former school, but seeks a genuine acknowledgement of the wrong committed.

“People say it’s all in the past,” Jeremy says, his voice laced with pain. “But my body keeps bloody well remembering.” His story is a stark warning, a testament to the enduring trauma of a practice built on prejudice and pain, and a powerful call for lasting change.