Dr. John Weiser has dedicated his career to combating HIV, witnessing the epidemic’s devastating impact since the 1980s. His work extended to leading the CDC’s Medical Monitoring Project, a crucial nationwide survey informing the country’s HIV response for over two decades.

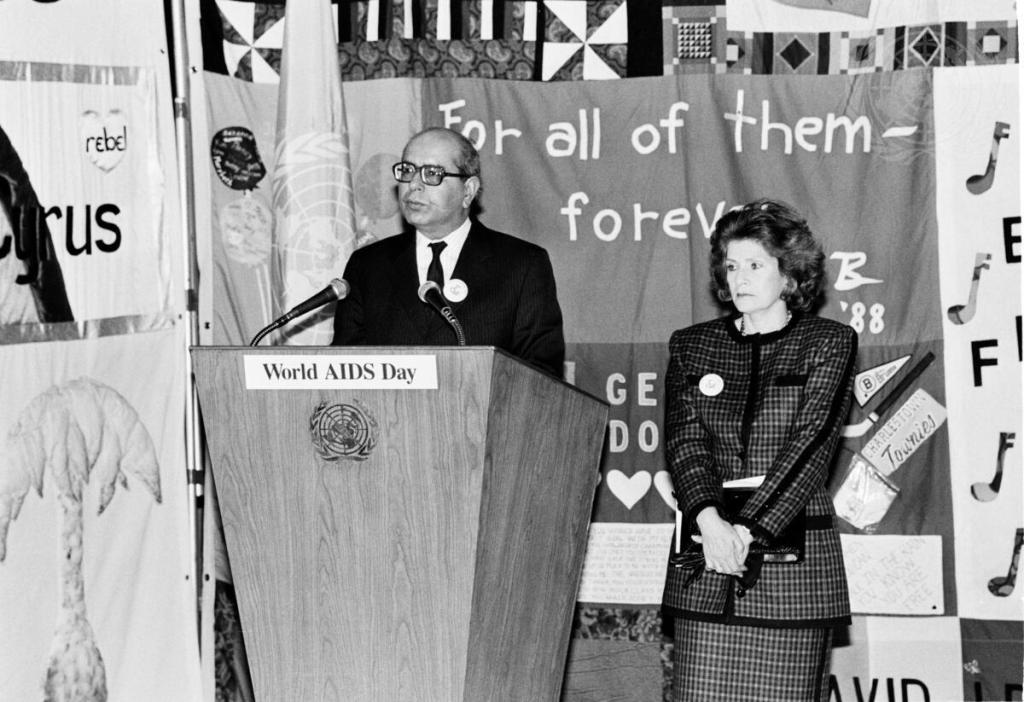

But a chilling shift occurred. The Trump administration not only censored the project’s findings but ultimately halted its funding, a blow delivered on the eve of World AIDS Day – a day the U.S. government, for the first time in decades, failed to formally acknowledge.

Weiser’s own experience mirrored this unsettling trend. Fired during mass layoffs, briefly rehired, and ultimately resigning, he returned to direct patient care at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Prior to his departure, he publicly warned against complying with orders to suppress scientific data concerning transgender individuals.

The crisis began with executive orders early in the Trump presidency, directives that sought to exclude gender identities not aligning with assigned sex at birth from federal research and reporting.

The impact was immediate and far-reaching. Researchers were instructed to scrub mentions of gender and transgender people from published and pending studies, and to cease collecting data on gender identity altogether. Even established terminology was altered, replacing “men who have sex with men” with the more restrictive “males who have sex with males.”

This directive descended from the highest levels, leaving no room for debate or dissent within the CDC. Compliance was expected, unquestioned.

One critical study, utilizing data from the Medical Monitoring Project, revealed a strong link between opioid misuse and increased HIV transmission risk. It also highlighted the severe lack of substance abuse treatment available to those living with HIV.

However, when Weiser submitted the paper for clearance, he was ordered to remove data specifically concerning transgender individuals. He refused, recognizing the fundamental harm of suppressing data for ideological reasons and the betrayal it would represent to his patients.

He withdrew the paper, leaving vital information unpublished. He understood that erasing data equates to erasing people, denying their existence and hindering efforts to improve their care.

His transgender patients already face immense challenges – poverty, housing instability, mental health struggles, and pervasive stigma. Denying them recognition, he believes, only exacerbates these burdens, hindering their ability to find comfort and health.

One patient, fearing increased visibility and potential harm, even considered further surgical procedures simply to feel safer in public. Her concern wasn’t political; it was a matter of survival.

The CDC’s compliance, Weiser believes, stemmed from a misguided hope that appeasement would protect other programs. That hope proved false. Funding for the Medical Monitoring Project was terminated, and fears grew that all HIV prevention and surveillance funding could be eliminated.

He worried about a dangerous precedent: if data could be suppressed based on gender identity, what would prevent similar censorship regarding immigration status, homelessness, or even race? Where would the line be drawn?

Some clinics and organizations began to contemplate curtailing services to vulnerable populations, fearing the loss of federal funding. They faced impossible choices, weighing the needs of their programs against the well-being of those they served.

Weiser’s advice to these leaders was stark: compromising on principles, even with good intentions, ultimately undermines scientific integrity and harms everyone. He drew a parallel to the rise of autocracy, citing journalist Masha Gessen’s observation that such compromises are often rationalized as necessary to protect institutions or livelihoods.

Gessen argues that this gradual erosion of principles is precisely what allows authoritarian power to solidify. It’s a slow surrender, masked as pragmatism.

Ultimately, Weiser resigned from the CDC because he realized he could do more good by focusing on the individual patients he treated. Numbers, he said, represent real people, people whose suffering he witnesses firsthand.

When you know someone, they cease to be an abstract data point. They become a human being deserving of care, dignity, and truthful representation.