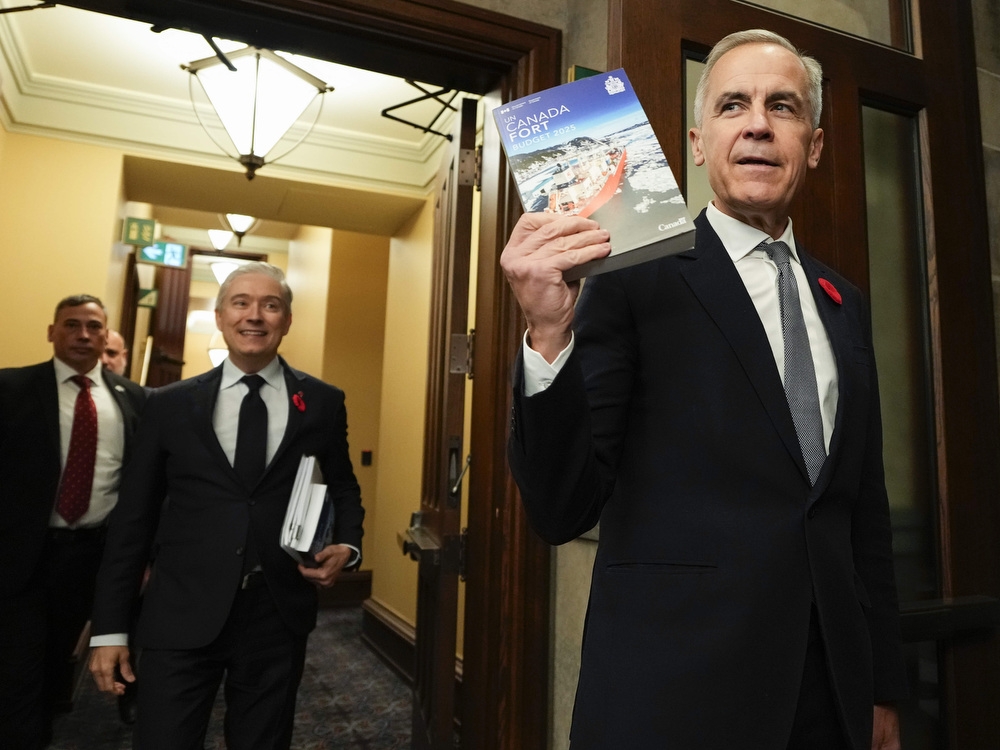

The Prime Minister had just delivered a budget framed as a necessary tightening of belts. Yet, within hours, a different scene unfolded in the heart of Ottawa – a celebration brimming with champagne and self-congratulation. Finance Minister Francois-Philippe Champagne, surrounded by a sea of smiling faces, took a “victory lap” at a lavish post-budget party.

The event, hosted by a media outlet and a prominent lobbying firm, wasn’t a secret. It was documented, photographed, and detailed in a glowing report. Attendees included a remarkable collection of political insiders: cabinet ministers, MPs, lobbyists, bureaucrats, and journalists, all basking in the afterglow of a budget impacting the lives of everyday Canadians.

Champagne himself addressed the crowd from atop a booth, his voice ringing with enthusiasm as he proclaimed “Vive le Canada!” before posing for selfies and accepting accolades. A seasoned Ottawa journalist described it as typical for such occasions, but for many, the timing felt profoundly out of touch.

The celebration illuminated a deeper issue, one described by a veteran civil servant as the insidious rise of the “Ottawa bubble.” This isn’t a story of overt corruption, but a subtle shift in power – a quiet takeover of the conversation between government and citizens by a network of think tanks, lobbyists, and those within the political sphere.

This ecosystem thrives on familiarity and mutual benefit. Former political staffers seamlessly transition into lucrative consulting roles, and the same perspectives circulate endlessly between policy-making offices and influential think tanks. It’s a “closed epistemic circle,” where dissenting voices are often muted by politeness and shared understanding.

Politicians find this system appealing because genuine public consultation is often messy and time-consuming. Journalists rely on readily available, “credentialed” sources within the bubble, creating a feedback loop where policy and its coverage are shaped by the same select voices. It’s a matter of convenience, but the cost is significant.

The consequence is a growing disconnect between the government and the governed. As public opinion is filtered through layers of intermediaries, the authentic voices of citizens are reduced to “PowerPoint bullets.” This erosion of direct engagement breeds cynicism, declining voter turnout, and a simmering sense of frustration.

Canadians who feel unheard eventually stop speaking, and politicians who stop listening begin to simply manage the narrative. The distance between those who govern and those who are governed widens, creating a permanent chasm. The celebration in Ottawa wasn’t just a party; it was a stark illustration of a democracy slowly outsourcing its own thought process.