In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, a secret mission unfolded. Canada’s oldest corporate document, the royal charter of the Hudson’s Bay Company, was carefully loaded onto a private plane in Toronto. This wasn’t a routine shipment; it was the safeguarding of a 350-year-old piece of history.

The charter, penned on delicate animal skin, required precise conditions for its journey. Not too warm, not too cold, and shielded from harsh light, it was entrusted to a dedicated team – a company employee, a paper conservator, and an armed security detail whose vigilance never wavered. The destination: Winnipeg, a 1,500-kilometer flight carrying an irreplaceable artifact.

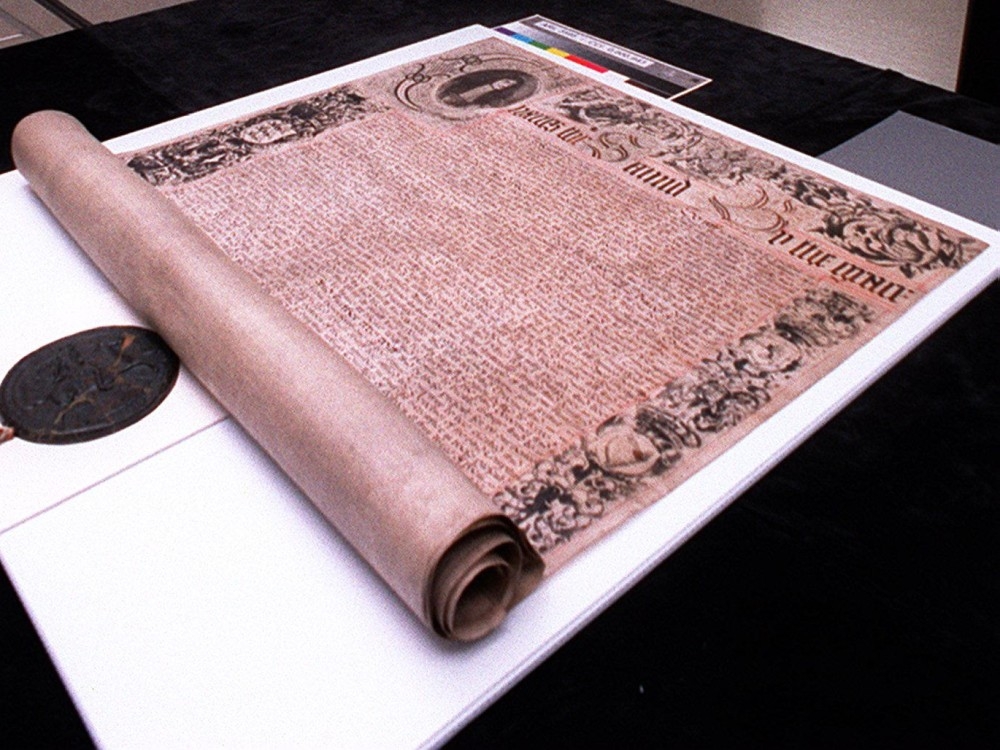

Upon landing, the charter was immediately escorted to the Manitoba Museum. There, gloved conservators meticulously examined every millimeter of the five-page vellum document and its ancient wax seal, documenting its condition and any potential damage sustained during transit. This wasn’t simply transport; it was a delicate operation demanding the utmost care.

“Some artifacts are relatively easy to loan and ship,” explained Amelia Fay, director of research at the museum. “But this one… this requires added layers of protection.” It wasn’t going through standard postal services; the stakes were far too high.

The extraordinary measures taken to move the charter revealed the immense responsibility now shared by four institutions. Following the Hudson’s Bay Company’s insolvency, the charter’s future was uncertain, demanding a level of preservation rarely seen.

The story unfolded through interviews with a dozen experts, employees, and government officials, many speaking anonymously while the charter’s fate was being decided. Ultimately, the Thomson and Weston families stepped forward, purchasing the charter for $18 million with a plan to ensure its public accessibility.

The purchase was approved by the courts, paving the way for a unique arrangement. The charter would be donated to The Archives of Manitoba, the Manitoba Museum, the Canadian Museum of History, and the Royal Ontario Museum – becoming its permanent custodians, shared for generations to come.

This document isn’t merely an artifact; it’s arguably the most significant treasure from the Hudson’s Bay Company’s vast collection. It predates Canada itself, issued by King Charles II in 1670, and laid the foundation for the fur trading empire that shaped the nation and its relationship with Indigenous peoples.

The charter granted HBC control over a staggering one-third of modern Canada, influencing Indigenous relations for decades. Remarkably, it’s the oldest surviving record from the company’s early years, as meeting minutes from 1694 reveal that records from its first four years of trade mysteriously vanished, “carryed away by one of their servants.”

For centuries, the charter’s location varied. Before its recent display in Winnipeg, it resided in a glass case at HBC’s Toronto headquarters, largely unseen by the public. Only a select few historians and business associates had ever laid eyes on this pivotal piece of Canadian history.

Crafted from five sheets of meticulously inked animal skin, the charter is remarkably durable, possessing a potential lifespan “in the thousands of years,” according to archival consultant Laura Millar. The first page boasts a portrait of King Charles II, England’s coat of arms, and ornate flourishes, all framed by a thick border.

The wax seal, once a vibrant green, now a darkened brown with age, bears the Great Seal of England, held in place by fragile silk laces – remnants signifying the document’s intended perpetuity. Sadly, fragments of the seal have broken off and are now stored separately, a testament to its delicate state.

The charter also bears the marks of time and preservation attempts. Cracks have been repaired with pins and nails, and wormwood was once applied to enhance legibility, ironically creating illegible blotches on the ancient script. This incident occurred during the 304 years the charter resided in England.

Before crossing the Atlantic, the charter was secured in iron chests at HBC’s British headquarters. Rumors even suggest a brief stay at Windsor Castle, though definitive proof remains elusive. However, it’s confirmed that the charter was safely stored at Hexton Manor during the looming threat of World War II, protected from potential bombing raids.

In 1974, the charter returned to Canada by plane, meticulously measured and weighed for transport. The accompanying waybill, marked with urgent instructions – “RUSH RUSH RUSH!!!!! MUST RIDE. BOOKED DIRECT FLIGHT.” – valued the artifact at £25,000 (approximately $442,000 today). The flight itself cost a mere £63.48.

Upon arrival, it was displayed under glass in HBC’s boardroom, later upgraded to a “more superior” case in 1997. The fate of the original iron chests and the Queen Elizabeth II display case remains unknown, lost to the passage of time.

Preserving such a treasure is a complex undertaking. Constant security, controlled lighting to prevent ink fading, and stable temperatures are essential. Even slight vibrations can damage the fragile seal, requiring careful padding and protection during transport.

The Canadian Conservation Institute has conducted multiple examinations of the charter, advising on its transportation and display. Experts recommend considering the time of year to avoid extreme temperatures and meticulously planning the route, vehicle selection, and protective measures.

The Manitoba Museum’s 2020 exhibition featured the charter on a slight incline, deemed too fragile to hang vertically, within a state-of-the-art display case. Every movement, even an inch, required gloved hands to prevent oil transfer, with regular reports documenting the charter’s response to changing conditions.

The museum’s extensive HBC collection, including a birchbark canoe and a flintlock trade gun, provided a fitting context for the charter’s temporary display. Though the pandemic limited public access, the exhibition marked a rare opportunity to view this historical treasure.

Now, with the Thomson and Weston purchase finalized, the charter’s return to Winnipeg awaits. A final assessment by the Canadian Conservation Institute will determine the safest transport method, supported by a $5 million donation for its care.

The future will be shaped by a consultation mandated by the Thomson and Weston families, involving Indigenous communities, experts, and the public. While a timeline remains uncertain, one thing is clear: the charter’s preservation demands careful consideration, ensuring this remarkable piece of history endures for centuries to come.